By: SotiriosTheofanis and Maria Boile*

1. IntroductionContainer Shipping has experienced during the last three years a situation that is more complex and, potentially, more severe than the 2008 crisis that affected badly liner shipping, among other shipping sectors. Unlike the fact that following the 2008 collapse the market recovered soon andexperienced two spot upsurges in the years 2010 and 2013, currently the container shipping situation looks more gloomy and sustained in terms of crisis duration.

Quarterly results published by the leading container shipping companies saw a substantial erosion of financial performance. For instance, Maersk Line show a year to year Q1 revenue drop of 20% and a year to year drop of EBIT of 98%, while Cosco Container Line reported a revenue drop of 13%. Revenue per TEU values have also eroded substantially for most of the major players (Drewry Container insight, May 2016).

This article attempts to provide some more specific factual information, along with some insights on the root causes of the present situation and its potential implications on directly connected transportation industry sectors, including but not limited to ports.

2. Market Conditions

Global economic stagnation and the relatively low growth rates of the Chinese economy, as the global economic driver, along with a very ambitious supply adding program, have led to severe distortion of the supply and demand equation in the container shipping industry.

Global container transport demand has increased only by 1.1% in 2015 and it is anticipated that will increase only by 2.1% and 2.9% in 2016 and 2017 respectively. This is far below the expectations of the container shipping lines that have based their container capacity building plans on a sustained average annual demand increase of around 5%.

Container shipping carrying capacity has escalated from 5 million TEUs in 2000, to almost 20 million TEUs in 2015, an increase that has not been coupled by an analogous increase in demand, after 2013.

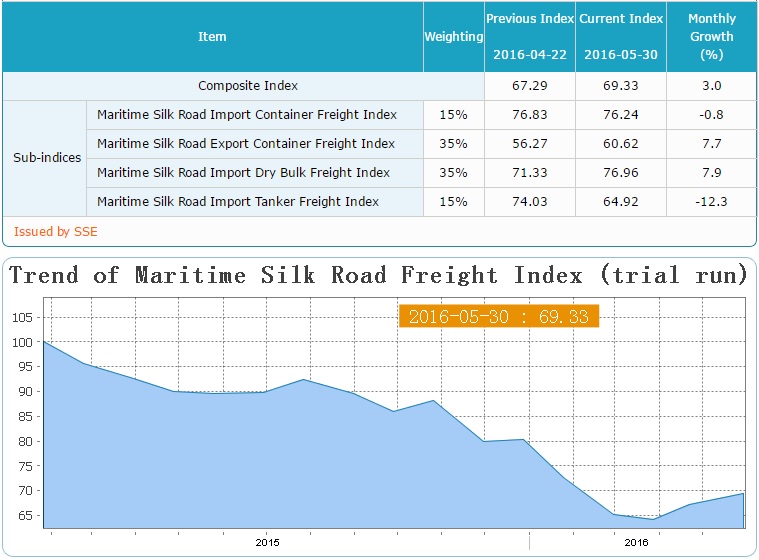

This situation has led container shipping companies to a serious price war that has driven revenues below costs in most cases. This price war extends to other shipping sectors, as can be deduced from the evolution of the Maritime Silk Road Index in Figure 1, but it is the first time that the container shipping industry acts as a “price taker”, i.e. in a behavior similar to that of other commodity shipping sectors, as compared to its traditional role as “price maker”, i.e. a price setting sector where competition relates mainly to service quality.

Figure 1: Maritime Silk Road Freight Index

(Source:http://en.sse.net.cn/indices/nmsrnew.jsp)Shipping lines try to keep relatively high slot utilization rates in the headhaul leg, by eliminating certain voyages, but, nevertheless, the backhaul trips are highly imbalanced with unacceptably low utilization rates. For instance, in November 2015 the headhaul (westbound) leg of the Asia-North Europe container trades reached an acceptable 82%, but the backhaul (eastbound) leg managed a poor 54% only. Though trade imbalances is not a new phenomenon in container shipping, in the present price war situation the effect of imbalances may be absolutely critical.

Low fuel prices have contributed in maintaining a precarious financial situation that could be relatively controlled. Nevertheless, the recent sharp increase in oil prices (from around 36 US$ in mid February 2016 to 48.4 US$ in mid May 2016) will pose a serious viability challenge to container shipping companies.

Low fuel prices have weakened operational practices like slow steaming to lower cost and keep going otherwise laid up capacity.

3. Ultra Large Container Vessels

Escalating vessel carrying capacity is a symptom of the last five years in the container shipping industry. Seeking economies of scale in building and deploying Ultra Large Container Vessels (ULCVs) led to vessels in operation with capacity of approximately 19,200 TEUs (MSC Oscar Class).

Average annual vessel capacity growth between 2011 and 2015 has escalated to an irrationally high of 15.3%, while the relevant figure for the period between 2001 and 2008 was only 1.9%.

Reliable calculations made relatively recently have shown that beyond the capacity of 14,000 TEUs no significant economies of scale are achieved, relating to vessel capacity, though economies of scale relate to bunker price, while indirect costs (e.g. terminals’ CAPEX and OPEX) are escalating.

Finally, it is interesting to note that container vessel capacity of vessels exceeding 19,000 TEUs carrying capacity entered the market in 2015 exceeded 170,000 TEUs.

4. Container Shipping Concentration and Alliances

Concentration in container shipping is a well-established trend during the last twenty years with growing scale and service network density. The global market share of the twenty top container shipping companies increased from 78% in 2005 to 87% in 2015, leaving a lean 13% for the rest of the players.

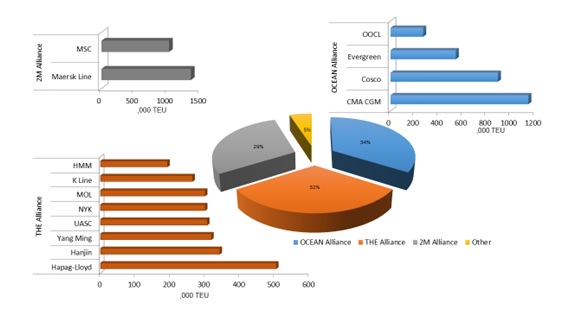

Following the merger of COSCO Group with China Shipping Container Line to form the giant carrier COSCOCS and the takeover of APL by CMA CGM, again COSCO in its new form decided to establish a new shipping alliance along with CMA CGM, OOCL, and Evergreen. The name of the new Alliance is “Ocean Alliance”. Subsequently, the remaining eight container shipping companies of the Alliances G6 (MOL, Hapag-Lloyd, NYK, HMM), CHKYE (Hanjin, K Line, Yang Ming), and Ocean Alliance (UASC) announced a new Alliance, called THE Alliance, potentially being “forced” by the new market environment . It is not yet clear whether the financially striving HMM (Huyndai) will join THE Alliance or not .THE Alliance will be operational in April 2017. This is a move towards higher concentration in global container transportation, replacing the four Alliances (2M, O3, CHKYE, and G6) with a three alliance scheme.

As it can be seen from the Figure 2, the capacity shares of the Alliances in the East-West trades are 29%, 32%, and 34% respectively for 2M, THE Alliance, and OCEAN Alliance, with only a 5% left for the rest of the carriers (Zim, Hamburg Süd etc.). It is more than evident, that this reality leads to a stronger oligopolistic situation for mainliner trades and hub selection, which maybe goes beyond the influence of the regulating authorities.

Figure 2: Container Shipping Alliances Capacity in East – West Trades

(Compiled from Drewry Container Insight, May 2016)5. Wider Sector Implications

The widespread deployment of ULCVs, the growing consolidation through alliances and mergers, as well as the operational and tactical decisions taken by the shipping lines to address cost cutting challenges and surplus capacity deployed resulting in reduced fleet utilization has certain serious impacts on the other container supply stakeholders and particularly ports and terminal operators.

Bigger vessels mean on the one side serious capital expenditures to cope with them in terms of seaside port capacity and equipment and on the other side increased operating costs to deal with cargo surges.

For instance, the dimensions of the Ship to Shore (STS) cranes have grown dramatically. Lifting height grew from 25.0 m (Panamax size) to 52.0 m (Triple-E size), and, respectively, the outreach from 37.0 m to 72.0 m and the rail-gauge from 15.0 m to 30.5 m.

Shipment sizes increase, which in certain ULCV calls reach 4,000-5,000 TEUs, poses severe resource and productivity constraints both on the seaside as well as on the landside operations.On the other hand, the deployment of bigger vessels leads to the so called cascading effect, i.e. the gradual replacement of medium sized vessels in the mainliner services by ULCVs and the “push” of medium sized vessels to feeder operations. Therefore, even feeder ports face infrastructure and equipment challenges, due to this increase in size of container vessels calling at them.

Another very serious implication is the fact that container shipping lines minimize the number of port calls of their mainliner services to cut costs and keep their slot utilization rates reasonably high.An example of the process of the gradual marginalization of container ports is that of the Port of Taranto in Italy. Taranto Container Terminal provides a negative, yet interesting, case on how changes in the interests of shipping lines can influence the fate of a given port. Taranto Container Terminal was developed in 2001 by Evergreen as a West Mediterranean hub. The terminal reached its throughput annual high record in 2006 (892,000 TEUs). In the year 2008, Hutchison Port Holdings (HPH) acquired a 50% stake of the terminal’s operating company in exchange for a stake in London Thamesport and ECT Delta in Rotterdam. In February 2014 Evergreen joined CHKY Container Shipping Alliance and moved its hub operations from Taranto to the Port of Piraeus. Subsequently (October 2014), Evergreen dropped its Asia-West Med mainliner service calling at Taranto and decided to serve Taranto through a feeder service from Piraeus. In early 2015, Evergreen diverted its feeder service call from Taranto to the better located Bari. After that, in May 2015 Taranto Container Terminal declared bankruptcy.

On another maritime logistics area, this process of capacity concentration and marginal outcome in container shipping has changed substantially the well-established business models, practices, and strategies of using container equipment and repositioning empty containers . For instance, Maersk Line spends 1 billion US $ to move more than 4 million empty dry and reefer containers and employed the concept of “Non-Operating Reefer” (NOR) to reduce the cost of empty container repositioning, a business model and practice that would not be applied in any case 15years ago. These optimization strategies are coupled by a clear tendency towards vertical integration in container equipment production, leasing and transport. On the other hand, it is not known yet whether the massive fleet integration plan announced for THE Alliance will cover also container equipment sharing schemes that will drive substantially operating costs down.

Concentration in container shipping has implications for the terminal operation industry, as well. In fact, based on 2014 data the seven major Global Terminal Operators (APMT, HPH, PSA, DPW, TIL, CMHI, Cosco Pacific) cover more than 36% of the total global container port throughput, calculated on equity base.

6. What Next? – Concluding Remarks

It is unlikely that the present tough situation, which, according to leading shipping industry sources , may be worse and, definitely, more complicated than the 2008 situation, will be balanced through industry consolidation or tactical and operational measures, like postponing services or schedules and cutting capacity deployed in services.

Extending vessel newbuilding delivery schedules may ease the situation for the short term and, possibly, the midterm horizon, but obviously restoring a healthy supply and demand balance requires drastic capacity demolition programs. The Industry looks at the moment hesitant to employ such demolition strategic initiatives, perhaps due to the very low scrapping prices and the rate of demolitions is very low, far below the addition of new capacity, while limited at the same time to very old and low capacity container vessels. Demolished capacity in the year 2015 was only 1% of the total global fleet capacity, while the additional capacity that entered the market was 1.7 million TEUs.

Scrapping the old low capacity vessels, mainly employed in North-South trades, helps in cascading smaller East-West deployed vessels into North-South trades, by providing supply space for them. Nevertheless, still this is not a fundamental global solution.In conclusion, it is inevitable that the container shipping industry is losing money at the moment, and this can be directly attributed to the Chinese and global economic slowdown, along with the irrational addition of surplus capacity during the last years. Shipping history has taught us that these distorted market situations are rebalanced by the market forces themselves. Whether this will be accomplished in the near future or not, remains to be seen.

* Sotirios Theofanis is an internationally acknowledged Freight Transportation, Ports and Maritime Logistics Expert; Fellow, Rutgers University, NJ, USA.

Maria Boile is Associate Professor, University of Piraeus and Affiliated Faculty, CERTH/Hellenic Institute of Transport, Greece** δημοσιεύθηκε στο SHIPPING μηνός Ιουνίου 2016

Sidebar

16

Τρι, Απρ