Russian researchers find that, by the end of the century, the Northern Sea Route, which hugs the Russian coast opposite the Northwest Passage, could be navigable for more than half the year.

The Arctic is warming faster than any other region on Earth. As Arctic ice levels dwindle through hotter summers and milder winters, the region has opened up to the shipping and energy industries. A new study finds that one shipping route—the Northern Sea Route—could be navigable for more than half the year by the end of the century.

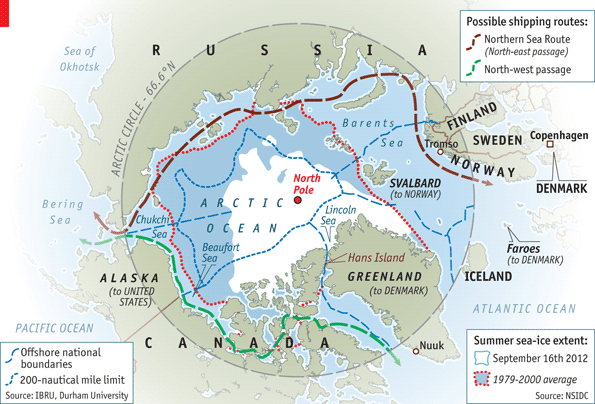

Parts of the Northern Sea Route, which runs along the Arctic coast of Russia opposite the better-known Northwest Passage, are called the Northeast Passage. The Northern Sea Route can cut the trip between Europe and Asia and North America in half, but, as Eva Holland reported for Pacific Standard last year, Arctic trade routes were once only a pipe dream:

For European monarchs and merchants in the 16th and 17th centuries, the newly “discovered” Americas presented a problem: They were an unexpected obstacle, one whose immense size was not yet fully known, falling square between the ports of Europe and the riches of the Orient. (The construction of the Panama Canal was centuries away.) And so the era’s geographers, who traded in theories at least as often as they did in maps and surveys, posited a theoretical solution: a Northwest Passage, running over the top of North America, and its twin, a Northeast Passage atop Scandinavia and Russia.Only in the last two decades, however, has climate change really opened up the Arctic to international shipping. In the new study, published today in Environmental Research Letters, researchers from Russia used climate models of sea-ice concentrations to predict what will happen to one optimal trade route along the Northern Sea Route in the future.

The team found that, under the climate scenario in which temperatures rise one to two degrees Celsius, the route will be navigable for a full four months out of the year. In a worst-case climate scenario, where temperatures climb by as much as four or five degrees Celsius, the route could be open for more than six months at a time. (It’s worth noting here that the latter scenario becomes far more likely should global leaders renege on their pledges under the Paris Agreement—the global climate accord that aims to limit warming to two degrees—as President Donald Trump has repeatedly threatened to do.)

But an iceless Arctic doesn’t necessarily mean smooth sailing. The authors point out that extreme winds and bigger waves will also become more likely along the Northern Sea Route. And as we wrote in October, accidents in the Arctic could amount to environmental disasters for the ecologically vulnerable region (not to mention the increased risks of sailing through a region where search-and-rescue operations are still inexperienced). Shipping along the Northwest Passage already appears to be affecting the behavior of narwhals, as Holland reported:

“We know that in the presence of shipping, we hear a lot fewer narwhal,” [Christopher Debicki, projects director at Oceans North Canada] says, cautioning that the work so far is “preliminary presence-absence studies.” But, he emphasizes, “We certainly know that, in the presence of loud anthropogenic noise, those stations are capturing a lot less narwhal sound. Which seems to suggest that they may be at least temporarily displaced by shipping.”

Of course, just because the route exists doesn’t mean that it will soon be clogged with shipping traffic—climate scientists are not in the business of predicting granular specifics about future trade routes and shipping traffic. But the opening up of the Northern Sea Route comes just as the icy relations between the United States and Russia appear to be warming up, and a new trade deal between the two nations could be in the works. Still, it’s too soon to know what such a deal might do to shipping practices along the route.Source: psmag.com

Sidebar

26

Παρ, Απρ